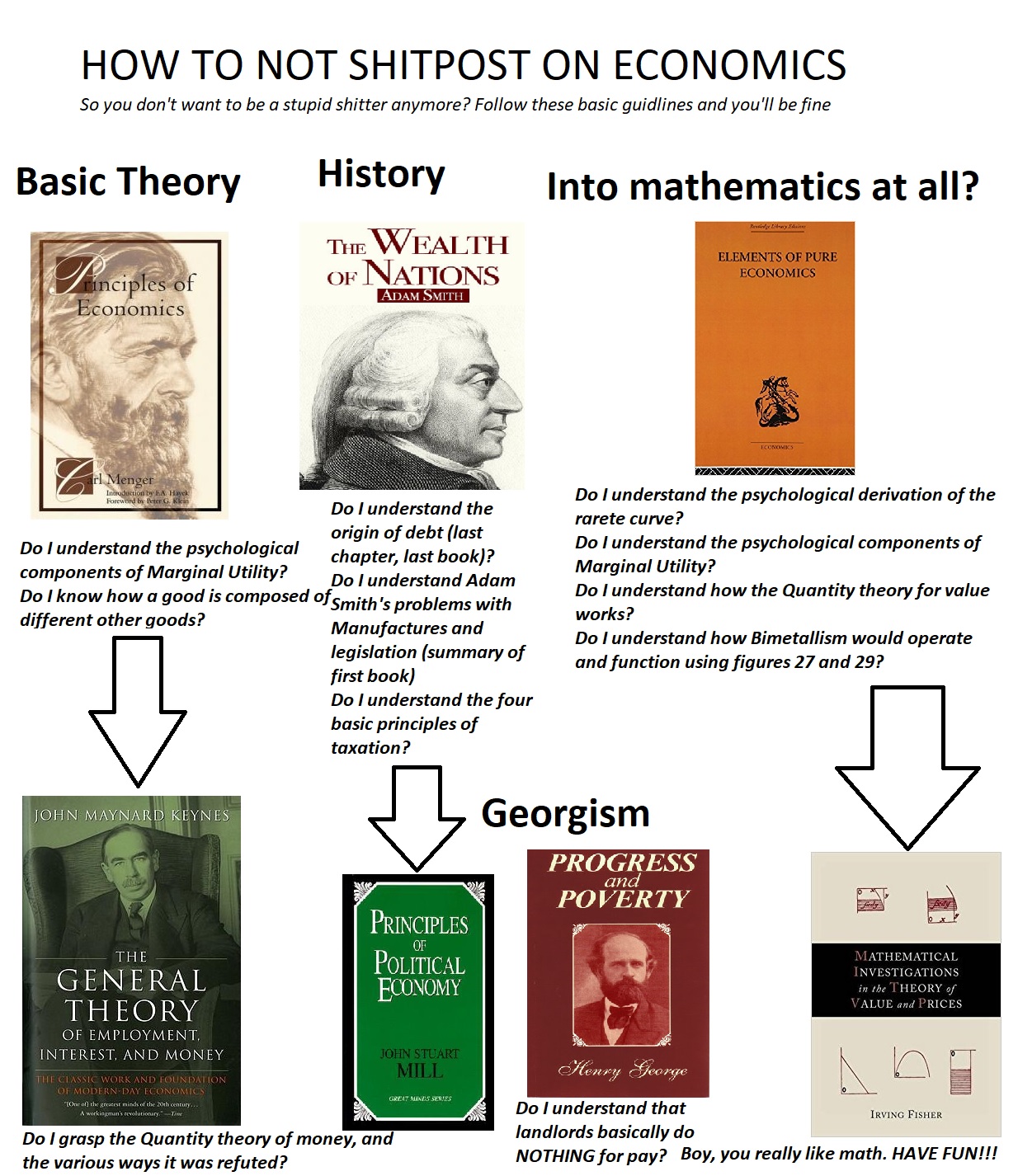

economics

Economics is a social science that studies how societies allocate scarce resources to satisfy unlimited wants and needs. It involves the analysis of production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services within a given system. Economists use various theories, models, and methodologies to understand and explain economic phenomena, such as supply and demand, prices, inflation, unemployment, and economic growth. The field is divided into microeconomics, which focuses on individual actors and markets, and macroeconomics, which examines aggregate phenomena at the national or global level. Key concepts in economics include opportunity cost, marginal analysis, incentives, market structures, and economic indicators. Economists often employ quantitative methods, including statistical analysis and mathematical modeling, to analyze data and test hypotheses. Economics also intersects with other disciplines, such as sociology, political science, and psychology, to provide insights into complex social and behavioral dynamics. Overall, economics seeks to provide a systematic framework for understanding and addressing real-world economic issues and informing policy decisions.

-

The father of general equilibrium theory and the grandfather of input/output analysis proves the Classical Economists right through value-neutral mathematics while criticizing their methods throughout. Leon Walras (1834-1910) is one of a kind and this book, translated by the able Walrasian scholar, Northwestern University's William Jaffe, is one of a kind.<br/><br/>Reading Professor Walras’ differentiating of art, science and ethics is alone reason to buy the book. “The Elements” was first published 140 years ago and appreciation of its 42 lessons still hasn’t reached its deserved level among economists not to mention the lay public. Its treasures remain largely buried under its mathematical notation and unintegrated with the modern-day economic psyche. Sad.<br/><br/>To witness a real scientist is to behold Walras proving J.B. Say correct without really wanting to do so. And, like all great scientists, Walras inevitably got himself into trouble with those living with sacred cows. Socialists dislike him because he proved private enterprise maximizes material well-being for all while libertarians dislike him because he dared say that efficiency might not be the end of the discussion.<br/><br/>There are reasons to question Walras’ scientific methods – mathematical treatment of a problem often involves making simplifying assumptions – as well as statements pregnant with political dynamite. Prof. Murray Rothbard, in his essay “Breaking Out of the Walrasian Box: The Cases of Schumpeter and Hansen,” is correct when he writes that mathematization tends to cut off “the messy and fuzzy uncertainties and inevitable errors of real-world entrepreneurship and human actions.” And this passage from “The Elements” (p. 61) is sure to raise eyebrows and provoke calls to French friends asking for the cultural context and questioning the accuracy of the translation – “Obviously all one can do about manifestations of the forces of nature is to identify, verify and explain them; but in dealing with workings of the human will, not only is it possible to identify, verify, and explain them, but having done that one can then control them.” Who or what is the “one” in that last sentence?

-

Irving Fisher was an American economist, inventor, and social campaigner. He was one of the earliest American neoclassical economists, though his later work on debt deflation has been embraced by the Post-Keynesian school. As a student, Fisher had shown particular talent and inclination for mathematics, but he found that economics offered greater scope for his ambition and social concerns. His thesis, published by Yale in 1892 as 'Mathematical Investigations in the Theory of Value and Prices,' was a rigorous development of the theory of general equilibrium. When he began writing the thesis, Fisher had not been aware that Leon Walras and his continental European disciples had already covered similar ground. Nonetheless, Fisher's work was a very significant contribution and was immediately recognized and praised as first-rate by such European masters as Francis Edgeworth.

-

In the beginning, there was Menger. It was his Principles of Economics that reformulated — and really rescued — economic science from the theoretical errors of the old classical school.Menger set out to elucidate the precise nature of economic value, and to root economics firmly in the real-world actions of individual human beings. In Principles of Economics, he advances the theory that the marginal utility of goods is the source of their value, rather than the labor inputs that went into making them. The implication of this theory is that the individual mind is the source of economic value — a point that touched off the marginalist revolution and started a departure from the flawed classical view of economics.For this reason, Carl Menger (1840–1921) is considered to be the founder of the Austrian School of economics. Principles of Economics is the book that Ludwig von Mises said turned him into a real economist. What's striking is how, nearly a century and a half later, the book still retains the incredible power of both its prose and its relentless logic.The Mises Institute's new edition features a new foreword by Peter G. Klein, which summarizes Menger's contribution and places him in the history of ideas. Klein also explains Menger's continued relevance in present times. F.A. Hayek contributes the introduction.Economics students still say that it is the best introduction to economic logic ever written. The book also deserves the status of a seminal contribution to science in general. Truly, no one can claim to be well read in economics without having mastered Menger's argument.

-

principles of political economy

with some of their applications to Social Philosophy

john stuart mill

The Principles of Political Economy with some of their applications to Social Philosophy by John Stuart Mill. Principles of Political Economy (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's death in 1873, and republished in numerous other editions. In every department of human affairs, Practice long precedes Science systematic enquiry into the modes of action of the powers of nature, is the tardy product of a long course of efforts to use those powers for practical ends. The conception, accordingly, of Political Economy as a branch of science is extremely modern; but the subject with which its enquiries are conversant has in all ages necessarily constituted one of the chief practical interests of mankind, and, in some, a most unduly engrossing one. That subject is Wealth. Writers on Political Economy profess to teach, or to investigate, the nature of Wealth, and the laws of its production and distribution: including, directly or remotely, the operation of all the causes by which the condition of mankind, or of any society of human beings, in respect to this universal object of human desire, is made prosperous or the reverse. Not that any treatise on Political Economy can discuss or even enumerate all these causes; but it undertakes to set forth as much as is known of the laws and principles according to which they operate.

-

Progress and Poverty

An Inquiry into the Cause of Industrial Depressions and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth; The Remedy

henry george

In Progress and Poverty, economist Henry George scrutinizes the connection between population growth and distribution of wealth in the economy of the late nineteenth century.<br/><br/>The initial portions of the book are occupied with refuting the demographic theories of Thomas Malthus, who asserted that the vast abundance of goods generated by an economy's growth was spent on food. Consequently the population rises, keeping living standards low, poverty widespread, and starvation and disease common.<br/><br/>Henry George had a different attitude: that poverty could be solved and economic progress preserved. To prove this, he draws upon decades of data which show that the increase in land prices restrains the amount of production on said land; business owners thus have less to pay their workers, with the result being mass poverty especially within cities.<br/><br/>The radical solution George proposes is a land value tax, whereby owners of land must pay a levy on their holdings. Thus money is diverted directly from landowners, to be spent on alleviating the poverty of workers, improving the infrastructure and environment of urban and rural areas, and even giving every citizen a basic income to cover their necessities.<br/><br/>George is also concerned with the cyclical nature of the economy, which by the latter part of the 19th century clearly followed cycles of boom and bust. This instability is further aggravated by spikes in land prices and consequently rents, whereby both producers - such as factory builders and farmers - and workers are displaced. Thus, Henry George doubles down on his idea for the land value tax, highlighting its efficiency and the fact that land - unlike resources or labor - is a fixed and easily quantified thing.<br/><br/>Divided into ten books, which in turn comprise between two and five chapters each, Progress and Poverty sequentially proposes, and discusses the implementations, of this economic reform. The book was enormously popular with the American public; written in a plain but engaging style, the powerful argument George makes would impact economists and the public consciousness alike for decades to follow.

-

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) is perhaps the foremost economic thinker of the twentieth century. On economic theory, he ranks with Adam Smith and Karl Marx; and his impact on how economics was practiced, from the Great Depression to the 1970s, was unmatched.<br/><br/>The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money was first published in 1936. But its ideas had been forming for decades ? as a student at Cambridge, Keynes had written to a friend of his love for 'Free Trade and free thought'. Keynes's limpid style, concise prose, and vivid descriptions have helped to keep his ideas alive - as have the novelty and clarity, at times even the ambiguity, of his macroeconomic vision. He was troubled, above all, by high unemployment rates and large disparities in wealth and income. Only by curbing both, he thought, could individualism, 'the most powerful instrument to better the future', be safeguarded. The twenty-first century may yet prove him right.<br/><br/>In The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), Keynes elegantly and acutely exposes the folly of imposing austerity on a defeated and struggling nation.

-

the wealth of nations

An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

adam smith

Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations was recognized as a landmark of human thought upon its publication in 1776. As the first scientific argument for the principles of political economy, it is the point of departure for all subsequent economic thought. Smith's theories of capital accumulation, growth, and secular change, among others, continue to be influential in modern economics.This reprint of Edwin Cannan's definitive 1904 edition of The Wealth of Nations includes Cannan's famous introduction, notes, and a full index, as well as a new preface written especially for this edition by the distinguished economist George J. Stigler. Mr. Stigler's preface will be of value for anyone wishing to see the contemporary relevance of Adam Smith's thought.